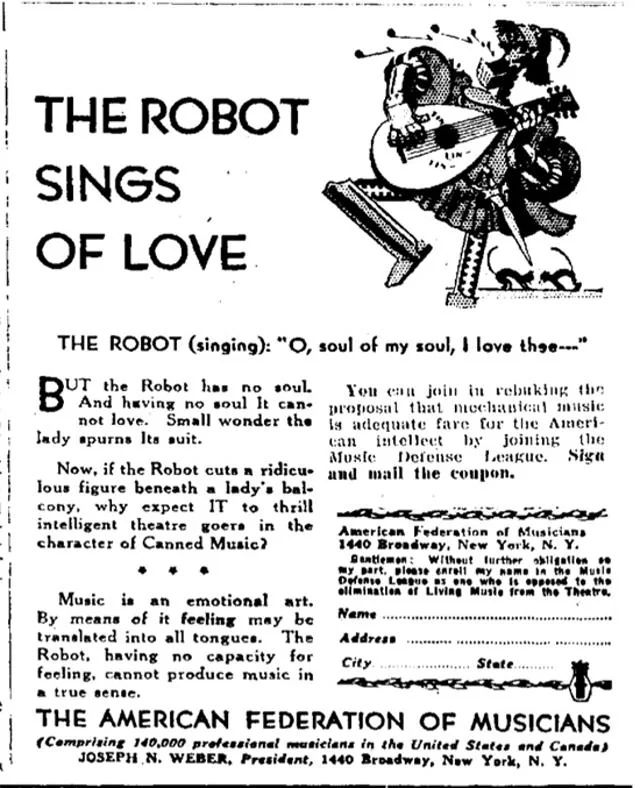

Advert from the 1930 campaign against recorded music by The American Federation of Musician.

Title: “Music Is a Necessity – Not a Luxury”: The 1930s AFM Campaign Against Recorded Music and Its Lasting Impact

Meta Description: Discover the American Federation of Musicians’ dramatic 1930s campaign against recorded music, its iconic “Canned Music” advertisements, and how this battle shaped the music industry.

Introduction: The Great Depression, Live Music, and the Rise of “Canned Music”

The 1930s were a tumultuous era for American workers. As the Great Depression wiped out jobs, musicians faced an existential threat: the rise of recorded music and radio broadcasts. These technologies threatened to replace live performances in theaters, cafes, and dance halls. In response, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), one of the nation’s most powerful labor unions, launched a fiery PR campaign demonizing recorded music as inferior and economically destructive.

This article explores the AFM’s provocative campaign, its iconic advertisements, and why this nearly century-old debate still resonates today.

The AFM’s 1930s Campaign: Fighting “Mechanical Music”

By the late 1920s, radio networks like NBC and CBS began using pre-recorded music (or “electrical transcriptions”) to cut costs. Jukeboxes and talking films also surged, displacing live orchestras. The AFM, led by President Joseph Weber, argued that “canned music” was stealing jobs from 250,000+ professional musicians.

To sway public opinion, the union rolled out newspaper ads, pamphlets, and slogans reframing live music as a cultural necessity—and recorded sound as greedy exploitation.

The Iconic Ad: “Music Is a Necessity – Not a Luxury”

One of the most striking AFM ads appeared in 1930, titled “Music Is a Necessity – Not a Luxury”. It featured a bold illustration contrasting two scenes:

- Left Side (“Canned Music”): A factory owner counting money while a worker stands idle, symbolizing unemployment caused by machines.

- Right Side (“Bread and Butter Lines”): Live musicians performing to support their families.

The ad declared:

“Real music is created solely by human skill and artistry. Mechanical music is inferior and robs musicians of their livelihood.”

Key arguments included:

- Economic Harm: Each jukebox or radio playback eliminated jobs for live bands.

- Quality Matters: Recordings lacked the “soul” and flexibility of human performance.

- Moral Duty: Supporting live music preserved American culture during hard times.

The AFM’s Tactics and Public Response

The union didn’t just advertise—it organized boycotts of venues using recordings. It also negotiated contracts requiring theaters to hire union musicians, even if their role was redundant. Some tactics succeeded; others faced backlash for stifling innovation.

Public opinion was mixed:

- For the AFM: Many patrons agreed live music was superior and pledged solidarity.

- Against: Critics called the AFM “anti-progress” and argued recordings democratized access to music.

Did the Campaign Work? Short-Term Wins, Long-Term Losses

In the early 1930s, the AFM secured concessions for musicians in film, radio, and dance halls. However, the campaign failed to stop the rise of recorded music—especially after World War II. Vinyl records, improved radio, and television cemented “mechanical music” as the norm.

Ironically, the AFM later embraced recordings. In 1942, it negotiated the Petrillo Ban, a strike forcing record labels to pay musicians royalties—a landmark win for artist rights.

Legacy: Lessons from the AFM’s Anti-Recording Crusade

- Labor vs. Technology: This was an early battle in the ongoing tension between automation and human labor—similar to today’s debates on AI-generated music.

- Defining Artistic Value: The AFM’s “music is human” argument foreshadowed modern discussions about authenticity in art.

- Union Power: The campaign showcased labor organizing’s role in protecting creative workers—a model still used by guilds like SAG-AFTRA.

Parallels Today: AI, Streaming, and Musicians’ Rights

The AFM’s 1930s fight mirrors current disputes. Organizations like the Music Workers Alliance now battle streaming platforms’ low pay and AI tools like voice cloning, echoing the AFM’s stance: technology should supplement artists, not replace them.

Conclusion: The Unending Debate Over Art and Machines

The AFM’s 1930s campaign against “canned music” was a desperate, creative, and ultimately flawed effort to protect livelihoods. While it couldn’t halt technological progress, it laid groundwork for musicians’ labor rights, fair pay, and the timeless truth that live performance holds irreplaceable magic.

As AI reshapes music again, the AFM’s rallying cry—“Music Is a Necessity”—remains relevant. After all, at its heart, music isn’t just sound: it’s human connection.

Keywords for SEO:

1930s recorded music opposition, AFM canned music campaign, Music Is a Necessity ad, history of musicians unions, labor vs. technology in music, Great Depression musicians, American Federation of Musicians history, mechanical music debate.

Image Suggestions for Content:

- AFM’s 1930 “Bread and Butter Lines vs. Canned Music” newspaper ad.

- Photographs of 1930s theater orchestras vs. jukeboxes.

- Joseph Weber, AFM president during the campaign.