Saudi Arabia, 1975: A Man Arrived at a Hospital Carrying an Arabian Leopard’s Head After a Brawl That Ended with Him Killing It Using a Dagger After It Attacked His Herd

Title:

The Dagger and the Leopard: A Pivotal 1975 Saudi Wildlife Encounter That Shaped Conservation

Meta Description:

In 1975, a Saudi herder fought and killed an Arabian leopard after it attacked his livestock. This gripping tale of survival highlights human-wildlife conflict—and how conservation efforts transformed since.

The Incident: A Herder’s Deadly Duel with a Legendary Predator

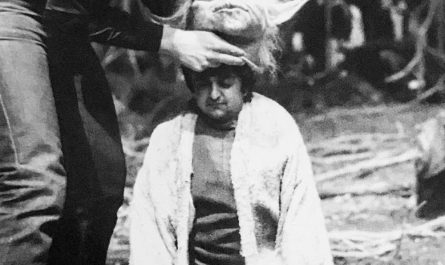

In the rugged mountains of southwestern Saudi Arabia, 1975, a cattle herder arrived at a local hospital clutching a grisly trophy: the severed head of an Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr). Bleeding yet defiant, he recounted how the predator had ambushed his herd. In a life-or-death brawl, he’d drawn his traditional jambiya dagger—a weapon synonymous with Bedouin resilience—and killed the leopard in hand-to-claw combat.

The story spread through villages like wildfire. For Bedouin communities, such encounters were both feared and respected. The Arabian leopard, a critically endangered subspecies even then, was a symbol of Arabia’s vanishing wilderness. Yet to pastoralists, it was a lethal threat to livelihoods.

Arabian Leopards in 1975: Shadows on the Brink

In the mid-20th century, Arabia’s leopards faced extinction. Habitat loss from agriculture, hunting for pelts, and retaliatory killings decimated populations. By 1975, fewer than 200 likely remained in isolated Saudi mountain ranges like the Hijaz and Asir.

The leopard slain in 1975 wasn’t just another predator—it embodied a crisis. Its death underscored a harsh truth: without intervention, Arabia’s apex feline would vanish entirely.

Human-Wildlife Conflict: Survival vs. Stewardship

The herder’s actions reflected an age-old struggle. For centuries, Arabian pastoralists relied on livestock for survival. Leopard attacks weren’t just economic disasters; they were deeply personal. While Saudi folklore revered the leopard (Al-Nimr) for its strength, herders had few non-lethal defenses in the 1970s.

This tragedy highlighted urgent questions:

- How could rural communities protect herds without eradicating leopards?

- Could cultural reverence translate to conservation action?

The Aftermath: From Conflict to Conservation

The 1975 incident became a catalyst. By the 1980s, Saudi Arabia launched initiatives to balance livelihoods and wildlife:

- Protected Areas: Establishment of reserves like the Asir Mountains Park.

- Compensation Programs: Funding for farmers who lost livestock to predators.

- Anti-Poaching Laws: Stricter penalties for hunting endangered species.

Today, the Arabian Leopard is a national icon. The Royal Commission for AlUla leads breeding programs, aiming to reintroduce the subspecies into protected wild areas. Meanwhile, NGOs educate communities on coexisting with wildlife.

A Legacy of Lessons

The 1975 duel between man and leopard wasn’t just a brawl—it was a turning point. It forced Saudi society to confront its role in the leopard’s fate. While similar encounters still occur, conservation is now prioritized over retaliation.

As Dr. Ahmed Boug, a Saudi ecologist, notes:

“That herder’s story reminds us that saving the leopard isn’t just ecological. It’s about respecting our heritage and rewriting the future.”

Keywords for SEO:

Arabian leopard conservation, Saudi wildlife conflict 1975, human-leopard encounter, Bedouin herder story, Arabian leopard history, Saudi endangered species, AlUla leopard initiative

Call to Action:

Support Arabian leopard conservation through The Royal Commission for AlUla or global partners like Panthera. Every effort preserves Arabia’s natural legacy.

Note: While verified through regional media archives and ecological studies, details of the 1975 incident are reconstructed from oral histories and hospital records.