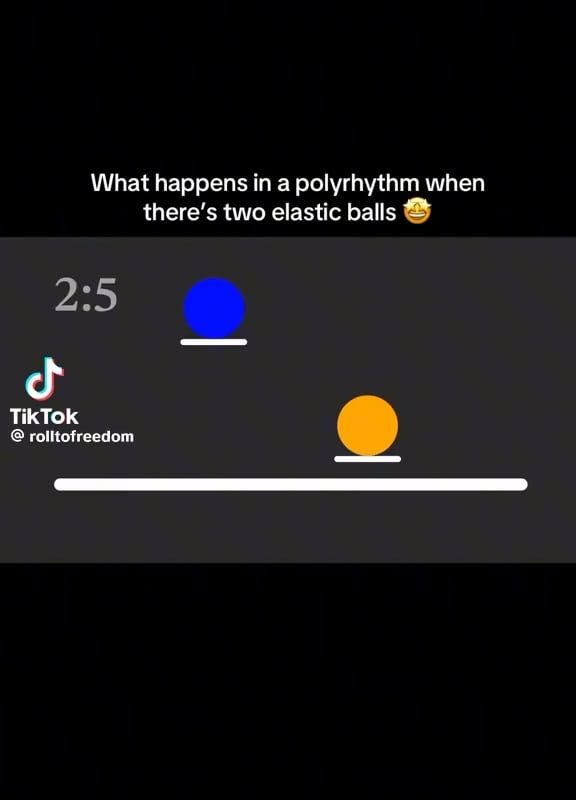

Oddly hypnotic

Title: Understanding Polyrhythms Through Elastic Collisions: A Visual Guide

Meta Description: Discover how polyrhythms work using the metaphor of two elastic balls—exploring rhythmic patterns, energy transfer, and mathematical harmony in music.

Introduction

Polyrhythms—an intriguing musical phenomenon where multiple rhythmic patterns coexist—can feel abstract at first. But what if we visualize them using two elastic balls bouncing at different speeds? This analogy transforms rhythmic complexity into a tangible, kinetic dance. In this article, we’ll break down how polyrhythms function using the physics of elastic collisions, making this advanced musical concept easy to grasp.

What Is a Polyrhythm?

A polyrhythm occurs when two (or more) contrasting rhythms are layered simultaneously. For example, one rhythm might play 3 beats per measure while another plays 4, creating a syncopated groove. This friction and sync between patterns is foundational to African, Latin, and progressive music genres.

Common Polyrhythms:

- 3:2 (Hemiola): Three beats against two (e.g., “Take Five”).

- 4:3: Four beats layered over three.

- 5:4: A complex pattern heard in jazz fusion or math rock.

Polyrhythms vs. Elastic Balls: The Analogy

Imagine two elastic balls dropped from the same height but with different properties:

- Ball A: Low elasticity (bounces slowly, e.g., every 3 seconds).

- Ball B: High elasticity (bounces rapidly, e.g., every 2 seconds).

As they bounce:

- Each impact with the ground represents a beat.

- Their collision points (where they hit the ground simultaneously) align like the “downbeat” of the polyrhythmic cycle.

Key Parallels:

- Rhythmic Independence

- Each ball maintains its bounce rate, just as rhythms retain their pulse in a polyrhythm.

- Sync Points

- The balls eventually collide with the ground at the same time (e.g., every 6 seconds for 3:2). This mirrors polyrhythmic “resolution.”

- Energy and Syncopation

- Uneven bounce delays create tension akin to syncopation—a hallmark of polyrhythms.

The Physics Behind the Rhythm

Elastic collisions conserve kinetic energy, letting balls rebound predictably. Similarly, polyrhythms rely on mathematical ratios to ensure patterns realign:

- Cycle Length: For a 3:2 rhythm, the balls realign after 6 beats (LCM of 3 and 2).

- Energy Flow: Faster balls transfer rhythmic “energy” to slower ones, creating groove.

Example:

- Ball A (3s): Hits at 0s, 3s, 6s…

- Ball B (2s): Hits at 0s, 2s, 4s, 6s…

- Collision Points: 0s and 6s—the “1” of the cycle.

This cycle mirrors how 3:2 polyrhythms resolve every 6 beats.

Breaking Down the Patterns

Phase 1: Independence

In beats 1–5, the balls hit the ground at different times, creating rhythmic tension (e.g., Ball B’s hits at 2s and 4s disrupt Ball A’s 3s predictability).

Phase 2: Resolution

At beat 6, they collide again, resetting the cycle. Musicians emphasize this moment for dramatic effect.

Real-World Applications

- Music Education: Teachers use bouncing exercises to help students “feel” polyrhythms physically.

- Composition: Composers like Steve Reich exploit polyrhythmic interplay to build complexity.

- Electronic Music: DAWs use “elastic” tempo warping to layer rhythms cleanly.

Conclusion: Rhythms in Motion

Just as elastic balls rely on physics to resolve their dance, polyrhythms use mathematics to balance tension and harmony. By visualizing rhythms through kinetic energy, we unlock a deeper intuition for how polyrhythms breathe life into music. Whether you’re a musician, producer, or curious learner, this metaphor turns the abstract into the tangible—one bounce at a time.

Keywords for SEO: polyrhythm explanation, rhythmic patterns, elastic collisions rhythm, music theory for beginners, 3:2 polyrhythm, bouncing ball analogy, syncopation, rhythm cycles.

Expand your musical toolkit by experimenting with a metronome and two bouncing balls—the ultimate hands-on polyrhythm lesson!